“The Good Earth”

Pearl S. Buck, circa 1931. (Wikipedia/Arnold Genthe)

“If you want to understand today, you have to search yesterday,” author and activist Pearl S. Buck is quoted as saying. To understand Buck’s work as the author of The Good Earth and founder of the organization that became Pearl S. Buck International, based in Bucks County, Pa., it is helpful to search her upbringing as the daughter of a missionary in China.

Buck (1892-1973) was the daughter of Absalom Sydenstricker, a Southern Presbyterian missionary, and Caroline Stulting Sydenstricker. When Buck was 5 months old, the family moved to China, eventually settling near Nanking; they chose to live among the Chinese people rather than in a missionary compound. Pearl S. Buck International’s biography of Buck notes that she “played with Chinese children and visited their homes … she later used this material in her novels.”

However, Buck also observed the suffocating effect of Absalom’s work on his relationship with his family, especially his treatment of Caroline. Buck’s mother had “accompanied her husband to China, where she was homesick for the remaining 40 years of her life,” writes Peter Conn in Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

“Carie’s emotionally impoverished marriage and exile provided Pearl a tragic example of the price that women pay for the loyalty to codes and customs that oppress them. It was the most important lesson Pearl would ever learn … [she] would not, as Carie had done, collaborate in her own defeat,” Conn writes. But he adds that, despite Buck’s rejection of her father’s religious beliefs, she inherited “his evangelical zeal, his sense of rectitude, and his passion for learning … she became, in effect, a secular missionary, bringing the gospels of civil rights and cross-cultural understanding to people on two continents.”

Conn writes of Buck’s mother, “Wherever she lived in China … Carie always made a flower garden. These were places of beauty and refuge, walled off from the Chinese streets that surrounded them.”

Asked whether this influenced the agrarian theme of The Good Earth, Conn tells this writer, “I thought of the gardens much more … in terms of a kind of emblem for the general disquiet and sense of loneliness that Pearl’s mother confronted, from the time she got to China until she died.”

VJ Kopacki, historic house director and curator for Pearl S. Buck International, adds that Caroline was “vibrant, thoughtful, and had a head full of ideas — and the only place in which she could express herself … was in that space of her garden. She could release some of that feeling of isolation and exile.” Kopacki observes that Buck “was an outspoken critic of the way that men, specifically American men, tended to treat their wives.”

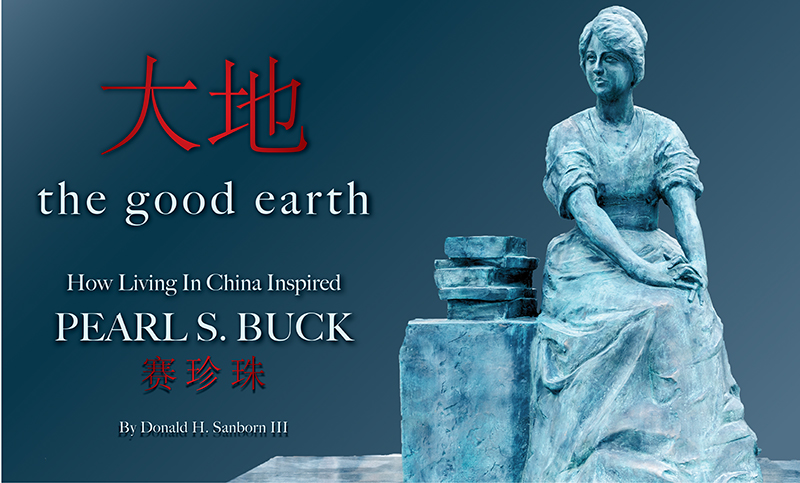

Sculpture of Pearl S. Buck’s novel “The Good Earth” in Pearl Buck Park in Zhenjiang, China. (Shutterstock.com)

“The Good Earth”

In 1931 Buck published The Good Earth, which became the best-selling novel in the U.S. in 1931 and 1932. It was written when she was living in China with her first husband, John Lossing Buck, an agricultural economist who specialized in the rural economy of China, and is set in Anhui, where the couple lived for several years. The Good Earth depicts the family of a farmer, Wang Lung, and his wife O-Lan. The family is confronted by many hardships, including famine and drought. O-Lan also contends with Wang Lung’s infidelity.

The Good Earth received the Pulitzer Prize in 1932. Buck was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1938 for “notable works which pave the way to a human sympathy passing over widely separated racial boundaries.” Pearl S. Buck International’s biography of the author notes that she was the “first American woman to be awarded both the Pulitzer and Nobel Prizes.” Conn adds that the novel was a “cultural phenomenon” that has been “translated into at least 60 languages.”

Asked about the extent to which a connection can be made between Buck’s upbringing and the writing of The Good Earth, Conn says, “The childhood provided Buck with a base, mostly linguistic and cultural.”

He notes that Buck’s knowledge of the Chinese language made her “almost unique” among Western travelers. “Most travelers, including most of the missionaries (excluding Buck’s father, who did learn the language, to his credit) depended on interpreters.”

Kopacki observes that Buck “wrote about people that she knew; her characters were drawn from the people that she met in her youth and adulthood. She probably couldn’t have written The Good Earth … with such clarity, or what is often cited as a fairly authentic voice (certainly for the time) of life in rural China, had she not lived there, loved her life there, and loved the people there.”

But Conn emphasizes the importance of Buck’s adulthood in China as well. He observes that Anhui province was at that time “considered one of the poorest regions of China.” He adds that living in a “rural community that depended on farming and was (like the characters in The Good Earth) always subject to drought, flood, and the occasional bandits … provided her with the material” for the novel.

Of the novel’s lasting cultural importance, Conn says, “In my book I talk about a study that was done in the early 1950s by a sociologist, Harold Isaacs, who published a book, Scratches on Our Minds. The purpose of the book was to determine where Americans acquired whatever they knew about India and China.

“Nearly 25 years after [Buck’s novel’s] publication, the most frequently cited source among Isaacs’ responders to the question, ‘Where did you acquire whatever you think you know about China?’ was The Good Earth. I don’t think I have ever been able to think of another book that had quite that kind of impact.”

A 1949 photo of Pearl S. Buck and two Welcome House children: Leon Yoder (in her arms) and David Yoder (the first Welcome House child). (Courtesy of Pearl S. Buck International)

Welcome House

“The test of a civilization is the way that it cares for its helpless members,” Buck is quoted as saying. In 1949 she founded the Welcome House adoption program, in response to the plight of children who were fathered, and frequently abandoned, by American servicemen in Asia. In the founding of Welcome House, Buck was aided by luminaries and Bucks County acquaintances such as author James Michener and Broadway lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II.

Pearl S. Buck International’s website notes that Welcome House was the first adoption agency specializing in the placement of biracial children, though changes in international adoption regulations led to the program’s cessation in 2014. Buck founded Welcome House after being unable to find a home for a 15-month-old because of his mixed-race background.

“There’s a line from Pearl Buck: ‘Nine months after a military occupation, you always have babies,’” Kopacki says, adding that for Buck — who, as early as the 1930s, had been an outspoken proponent of civil rights and a supporter of organizations such as the NAACP — the founding of Welcome House “was a natural progression from issues she already cared about.”

Conn adds, “She was also a lifelong student of power — and powerlessness. These ethnically mixed children epitomized powerlessness.”

Noting that at that time countries such as China required children to be registered in their fathers’ names, he continues, “In a legal sense, these children didn’t even exist.”

“In the patriarchal Confucian cultures of much of East Asia, such children were outcasts,” Conn explains. “First, because they didn’t have legitimate fathers. Second, because they were mixed race. So a lot of those children ended up on the streets, were abused, and many lost their lives. So Welcome House quickly became a resource for moving some of those children to the U.S., to try and find homes for them with American parents.”

Kopacki adds that for Buck, seeing “the way that Americans in particular were not taking responsibility for these children abroad … impacted her tremendously. She realized this was something she could change; she had an incredible amount of influence in the community.”

Conn remarks that, ultimately, Welcome House is a “manifestation of Buck’s deep, lifelong commitment to the welfare of children, and a concern with the dispossessed — in part because she had observed her mother feeling dispossessed. That actually is what The Good Earth is all about: what happens to ordinary people when they are confronted with a massive and irresistible force. It’s not a sentimental book; it’s a tough-minded book in which people suffer more than they prosper.”

Conn notes that his fourth child “was adopted from Korea through Welcome House, about 50 years ago. I encountered Pearl S. Buck through one example of her lifelong social and humanitarian activism.”

Pearl S. Buck, circa 1960. (Shutterstock.com)

Pearl S. Buck International

The website for Pearl S. Buck International states that the organization continues the author’s “legacy of bridging cultures and changing lives through intercultural education, humanitarian aid, and sharing the Pearl S. Buck House National Historic Landmark museum.” Kopacki explains that this is accomplished through education (tours at the museum), humanitarian aid, and multicultural programming.

Pearl S. Buck International is a continuation of the Pearl S. Buck Foundation, which the author created in 1964. The website notes that the foundation was chartered as “a child sponsorship organization to help children in their own countries with health, education, and job training.”

The Pearl S. Buck House is located on a 68-acre estate in Perkasie, Pa. In Buck’s time it was known as Green Hills Farm, and Kopacki notes that there are extant signs in Bucks County that refer to the property by that name. The beige stone farmhouse became the author’s home in 1934, three years after the publication of The Good Earth. It was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1980, and it has been a museum since 2002.

Kopacki explains that the house looked different when Buck arrived; the author made substantial alterations and additions to the architecture. “It’s still recognizable as the same house, but she made a lot of changes to it. It was something of a passion project for her. She adored the house, she lived in it for quite some time,” though “toward the end of her life she spent more time in Vermont.”

An ongoing tour at the museum is titled “Taking Action.” Kopacki says that the tour explores the “causes that Pearl S. Buck cared about — civil rights, women’s rights, rights for disabled people” with an emphasize on “how these issues are still impactful today.”

In March, in time for Women’s History Month, the museum launched “Dangerous Women,” a virtual exhibit. “It’s about women, like Pearl Buck, who were radical for their time,” Kopacki says, describing the exhibit’s subjects as “outsiders” who “took the initiative to change the world, even though it incited criticism — and even, in some cases, violence — against them.”

Of the humanitarian efforts of Pearl S. Buck International, Kopacki says, “We sponsor children in orphanages and in families, as well as kids going to college, to try and help them achieve their full potential. We work in multiple countries all over the world.”

Kopacki points to aid in response to the typhoons in the Philippines. “The typhoons did tremendous amounts of damage to homes … children were standing in six inches of water. That’s obviously not a safe or hygienic way for anyone to live.”

The organization solicited donations so that “the homes could be repaired.” Construction work, such as making roofs sturdier, was done so that “if this happens again, that the damage will be less severe.”

Kopacki adds that day-to-day assistance includes providing children with “health care, education, and psychosocial support.” The organization’s website offers viewers the chance to sponsor children from places including China, Kenya, and the Philippines.

Contemporary Relevance

Conn says that as he researched his biography of Buck, “I found myself engaged more and more with an extraordinary woman whose cultural significance was far-reaching for decades, however much it may have receded in the 21st century.” He considers Buck to be a “woman whose impact and very diverse, eventful, and consequential career should be better known.”

“Her story has quieted in recent years,” Kopacki agrees. “There’s still a generation of older people out there who know and love her, but I think younger people could really benefit from hearing her story, and seeing how it’s relevant for their lives, even today.”

Kopacki describes Buck as a “pioneer” of activism for causes for which the fight is “still ongoing,” and says that Pearl S. Buck International uses the author’s legacy to “spark conversation — to keep a dialogue going, and help people see how they, like Pearl Buck, might be able to change the world.”

To learn more about Pearl S. Buck International or to sponsor a child, visit pearlsbuck.org.