The Art of Making Simple Things Complex

Rube Goldberg, Rube Goldberg Inventions United States Postal Service Stamp (included on sheet of “Comic Classics” stamps), date unknown. Sheet of USPS stamps.

Celebrating the Comic Art of Rube Goldberg

By Ilene Dube

Among the earliest of John George’s memories is going to the Automat with his grandfather. “There was a whole wall of windows and all these little doors, and you would open one and take out your pie, and then a hand would come place a new piece of pie in the slot where you’d taken yours from,” recounts George, 73, a Skillman-based psychologist. “The whole thing was a big Rube Goldberg, a kind of inspiration for the world he put down on paper.”

In fact, John George’s grandfather, with whom he shared the Automat experience, was Rube Goldberg.

“The Art of Rube Goldberg,” the artist’s first retrospective in 40 years, is on view at the National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Philadelphia through January 21. The exhibit showcases his earliest published drawings and iconic inventions, political cartoons, and some material not previously exhibited, from original works of art and preparatory drawings to video.

Rube Goldberg, Concept Sketch of Boob McNutt, c. 1920s. Ink and pencil on paper.

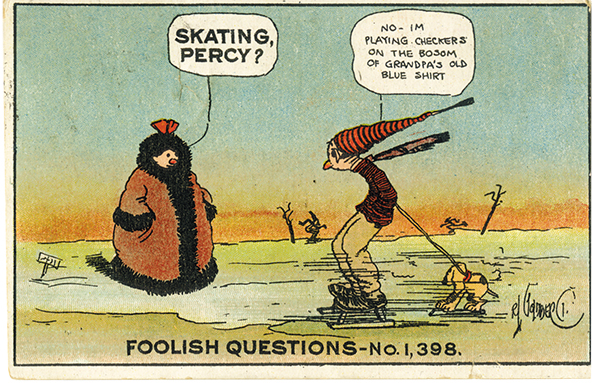

Highlights include one of Goldberg’s earliest existing drawings, The Old Violinist, from 1895 (he won a prize for it when he was only 12); an original concept drawing of Boob McNutt and Bertha from the 1920s; and original artwork for such daily and weekly comic strip series as Foolish Questions, Mike and Ike (They Look Alike), and Boob McNutt, all from the 1910s and 1920s. The influence of vaudeville and early film on Goldberg’s imagination is examined, along with his satirical takes on fashion, sports, politics, and gender roles.

Also included is footage from the Goldberg-scripted film, Soup to Nuts (1930), starring the Three Stooges; the classic self-operating napkin sequence from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936); and an interview with Edward R. Murrow.

“The internet and YouTube has given a whole new life to Rube Goldberg,” says his granddaughter Jennifer George, a jewelry and clothing designer who wrote a book about her grandfather, The Art of Rube Goldberg (Abrams ComicArts, 2013). “Any Rube Goldberg machine worth its salt goes viral on the web today.”

“iPhones are sort of black boxes by comparison with the machines that Rube Goldberg’s generation knew,” said The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, who wrote the introduction to The Art of Rube Goldberg. “So I also think that we look at Goldberg’s drawings with a certain amount of nostalgia for a lost era, when our machinery was at least lucid.”

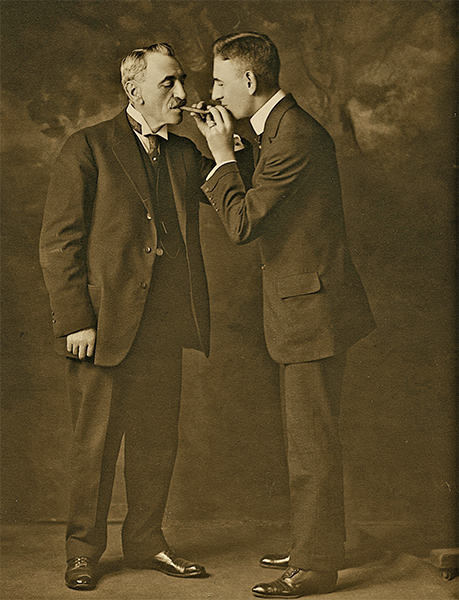

Rube Goldberg, Rube and Father Lighting Cigars, date unknown. Photograph.

John George is the son of renowned artist Thomas George (1918-2014), who spent much of his life in Princeton. Growing up, John George spent a great deal of time with his grandparents — at their Long Island Beach House, at their Upper West Side apartment and in his grandfather’s 57th Street studio — and describes his grandparents as a second set of parents. Goldberg would drive his grandson to activities, such as riding lessons. On the way home George would say “let’s get lost” to his grandfather, and Goldberg would oblige, taking a lesser known route. “He had a unique view of the world, with all its oddities and ironies, and provided a view of the world in which people made simple things complex,” says George.

Later, George would walk down the street with his grandfather and be reminded of the celebrity he was, counting among his friends the likes of Charlie Chaplin, Groucho Marx, George Gershwin, and Harry Houdini.

The greatest bit of wisdom passed from grandfather to grandson, George recounts, was “to laugh. Just to laugh. It’s a big part of being a healthy person.”

By the time he was 48, Rube Goldberg had become an adjective in Merriam-Webster’s dictionary: “accomplishing by over complex and humorous means what seemingly could be done simply; having a fantastically complicated improvised appearance.”

“It’s an illogical sequence of things put in a logical sequence,” Goldberg told Murrow in the interview screened in the exhibit.

While Goldberg never built the machines featured in his iconic invention drawings, visitors to the exhibition will experience an interactive area of the exhibition, where they can play with existing simple machines and even build their own Rube Goldberg.

Goldberg (1883–1970) was the most famous cartoonist of his time, syndicated in daily newspapers throughout the world. In his 72-year career (longevity runs in the Goldberg/George family), the cartoonist, humorist, sculptor, author, engineer, and inventor wrote and illustrated nearly 50,000 cartoons. But it is the Rube Goldberg devices for which he is most celebrated. Goldberg is considered a grandfather of STEM education, having blended science, technology, engineering, and math before the acronym existed. Rube also pioneered STEAM, with art playing a key role.

Born in San Francisco — his father was police and fire commissioner — the quiet, creative child began taking art lessons from a sign painter and in later years was proud that this was his only art training. Though he longed to pursue illustration as a career, his father insisted he study mining and engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. Engineers were the rock stars of the industrial revolution and Rube’s father wanted him to be a part of it, but Rube kept drawing. His work appeared in Berkeley’s humor newspaper and in his college yearbook.

Upon graduation Goldberg got a job with the San Francisco sewer system, but he left after six months, taking a huge pay cut to become a cartoonist for the sports section of the San Francisco Chronicle. A year later he became staff cartoonist for the San Francisco Bulletin. His The Look-Alike-Boys — a precursor to Mike and Ike (They Look Alike) — appeared in the color supplement to the Sunday paper.

Rube Goldberg, Foolish Questions Postcards, c. 1910. Color postcards.

The times they were a changin’ — the telephone heralded a new form of communication, and motion pictures were the new entertainment, to which people drove in automobiles. Airplanes inspired people to look up. “The Machine Age had arrived, clicking, churning, cranking, winching, and whizzing into our lives,” according to exhibition materials. “And there was no better, more discerning and satirical eye to comment on these trends than Goldberg.”

Believing New York to be “the front row,” Goldberg took a train east and moved to New York. With his wife, Irma, and two sons, Goldberg lived at 98 Central Park West. By 1922, a newspaper syndicate paid him $200,000, the equivalent of $2.3 million today, for his comic strips.

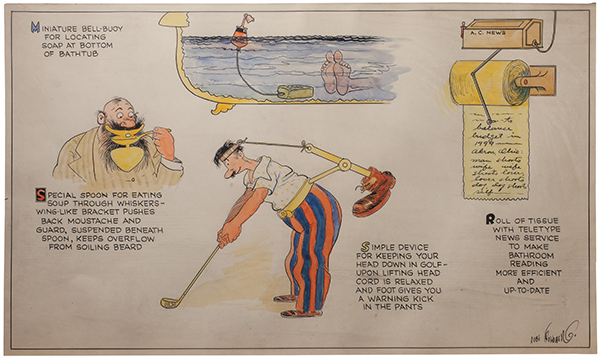

His first invention cartoon, The Simple Mosquito Exterminator — No Home Should be Without It, was published in the New York Evening Mail in 1912 (we could use one of those today!). The way Goldberg saw it, technology, intended to simplify life, only made things more complex. In 1914, his Automatic Weight Reducing Machine used a donut, bomb, balloon, and a hot stove to trap an obese person in a room without food, who had to lose weight to get free. His contraptions, though parodies of the increasingly automated world, were written and drawn in the dry diagrammatic style of U.S. Patent applications.

They contained pulleys, levers, birds, and rockets to fix simple problems like fishing an olive out of a tall jar, or remembering to mail a letter. Goldberg created the character/inventor Professor Butts as his alter ego. He continued drawing the inventions for 30 years, and while he also engaged in other forms of artistic expression, from songwriting to playwriting, acting to sculpting. He never thought that his invention cartoons would come to define his life’s work.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, educational shows like Sesame Street, Vision On, and The Electric Company routinely showed bits that involved Rube Goldberg devices, including the Rube Goldberg Alphabet Contraption, and the What Happens Next Machine. Wallace and Gromit; Pee-wee’s Big Adventure; Edward Scissorhands; Back to the Future; Honey, I Shrunk the Kids; and Home Alone, among others, owe a debt of gratitude to Goldberg.

Rube Goldberg, Inventions (Bell-Buoy, Soup Spoon, Golf), c. 1938-1941. Color ink and watercolor on paper.

“Most of us only hit the jackpot once,” cartoonist Al Jaffee told a 92nd Street Y audience, broadcast on Livestream. “But Rube kept creating new features every week that became wildly popular — he was extremely inventive.”

“If my grandfather were alive today, he’d still be a cartoonist,” says John George. “He would still find the ways in which people make simple things complicated. Back in the day, when we wanted to turn on the TV, we’d push a button. Now we have five remotes. He’d turn that into a cartoon. There’s nothing new under the sun. He saw it and took it to heart and shared it with the world.”

NMAJH is hosting a Rube Goldberg Machine Contest for high school-aged students. The contest requires students to build overly complicated and comically contrived inventions that complete a simple task. Student groups of five or more can register for NMAJH’s contest at rubegoldberg.com. Registration closes in November.

All Artwork Copyright © Rube Goldberg Inc. All Rights Reserved. RUBE GOLDBERG ® is a registered trademark of Rube Goldberg Inc. All materials used with permission. www.rubegoldberg.com