A Taste of New Jersey

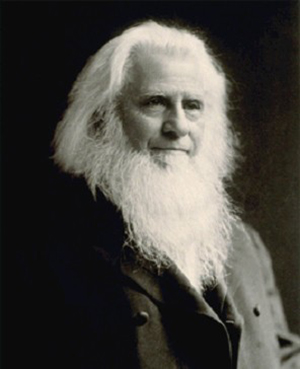

Breeder of the Rutgers tomato Lyman Schermerhorn (left) in a field of tomatoes (circa 1930s, others in photo unknown). Courtesy of Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station.

Bringing Back the Classic Tomato, Salt Water Taffy & More!

By Wendy Greenberg

Jersey tomatoes. The phrase conjures roadside stand baskets piled high with bright red tomatoes begging to be sliced, each bursting with flavor.

Tomatoes are among the foods that evoke New Jersey’s culinary richness, along with such disparate delicacies as cranberries, salt water taffy, pork roll, Welch’s Grape Juice, Campbell’s soups, Boylan’s Birch Beer, and other eminent edibles.

Behold the “classic” Jersey tomato: Defined by its “deep, red color inside and out,” it may have a large stem scar, “with cracks or slits, or yellow ‘shoulders,’” describes Cindy Rovins, agricultural communications editor at the Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station (NJAES). Considered “imperfect by today’s market standards, the flesh was smooth, firm, and juicy — not mealy or crunchy like modern supermarket tomatoes. The taste was full-bodied tomato flavor with the perfect balance of sweet and tangy.”

But over the years the tomato had drifted, flavor-wise. The stakes, so to speak, were high. After all, the Jersey tomato has a reputation to uphold. Enter the NJAES Rediscovering the Jersey Tomato program, an initiative that, in the last decade, has restored the taste to Jersey tomatoes.

The popular Rutgers tomato debuted in 1934, and, by the 1950s, comprised close to 70 percent of all U.S. tomatoes, say Rutgers agriculturalists. But it was developed without a patent and seed companies made changes over time. The result, as modern agriculture evolved, was that changes that boosted production, or made for sturdier shipping, ultimately sapped the flavor.

The Rutgers tomato, developed by vegetable breeder Lyman Schermerhorn, was the result of crossing the best processing tomatoes, in cooperation with Campbell Soup Company. Schermerhorn conducted field tests on New Jersey farms, with the resulting tomato a favorite of the state’s canning and food processing industries and the choice of U.S. commercial tomato growers through much of the mid-20th century, according to NJAES.

What happened, explains Thomas Orton, a professor of plant biology and head of the Rutgers tomato program, is that when agriculture shifted to a non-local economy, “the tomatoes had to be firm for shipping, no cracks.” Not only were the varieties often diffused, but the tomatoes supermarkets received year-round were far from the vine. “The good news,” says Orton, “is year-round produce, but the bad news was that it takes two to three weeks to get them here. Tomatoes were hard as rocks because they were harvested when they were still green then ripened in warehouses, and flavor was lost.”

Jersey tomatoes began to regain their status in 1968 when the Ramapo tomato was developed at Rutgers, and was embraced by home gardeners and commercial growers. But the Ramapo was later dropped from seed catalogs, as newer varieties were introduced, Rovins says. When the Ramapo developer, who was by then retired, sent NJAES the parent seeds, seed companies did not produce small batches for the home gardener market.

Jersey tomatoes began to regain their status in 1968 when the Ramapo tomato was developed at Rutgers, and was embraced by home gardeners and commercial growers. But the Ramapo was later dropped from seed catalogs, as newer varieties were introduced, Rovins says. When the Ramapo developer, who was by then retired, sent NJAES the parent seeds, seed companies did not produce small batches for the home gardener market.

Rutgers itself decided to get into the seed business. The Rediscovering the Jersey Tomato program has resulted in four varieties, sold through the Rutgers website: the Rutgers 250 tomato; the Ramapo F1 Hybrid tomato; the Moreton F1 hybrid tomato; and the KC 146 tomato, associated with Campbell’s Soup. The newest variety is the Scarlett Sunrise bicolor grape tomato. All emphasize flavor.

One serendipitous occurrence eight years ago helped bring back the original Rutgers tomato. The researchers at Rutgers did not have the parent seeds for the original tomato, so buying “Rutgers” seed did not guarantee the texture and taste of the original tomato. In 2010, Campbell’s was able to donate parent line seeds to Rutgers. The tomato was released in 2016, which happened to be the university’s 250th birthday. That tomato is now called Rutgers 250.

Today, Orton says, “there is renewed interest in flavor. There is improved availability of seeds for commercial growers and small acreage. New seed companies are addressing the demand. Even the average heirloom is very good now.

“People want the traditional culinary experience. Picked ripe locally and consumed in a day or two, the flavor is captured.”

For more information, visit njaes.rutgers.edu.

Dr. Thomas Bramwell Welch

Dentist’s Solution: Welch’s Grape Juice

Cumberland County takes pride in its juicy heritage. Its website chronicles how Vineland dentist, Dr. Thomas Bramwell Welch, a communion steward at Vineland Methodist Church, had encountered a visitor who drank too much wine.

As an alternative, in 1869 he gathered baskets of grapes from his trellises, and filtered, pasteurized, and bottled them. Pasteurization was a relatively new sterilization method using Louis Pasteur’s theory of fermentation. From 1869 to 1872 Welch produced unfermented wine for churches in southern New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania, and founded Welch’s Fruit Juice Company, first marketed as Dr. Welch’s Unfermented Wine. It became Welch’s Grape Juice in 1893.

Demand was great so a production area was set up in a barn, and later a factory at his second house, where the Vineland police building is now. Son Charles entered the business in 1872. Published accounts recount how, in 1913, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan served grape juice instead of wine during a diplomatic function. Eventually the family moved to Westfield, N.Y., where grapes were more plentiful. Welch’s is now headquartered in Concord, Mass.

Now Missing: Trenton Oyster Crackers

Walmart has pictures of them but says they are out of stock. A search on Amazon brings up other brands. Restaurants are serving pale imitations. The Original Trenton Cracker, aka OTC – the crunchy sphere-shaped crackers often served with oyster stews and fish chowders, seems

Walmart has pictures of them but says they are out of stock. A search on Amazon brings up other brands. Restaurants are serving pale imitations. The Original Trenton Cracker, aka OTC – the crunchy sphere-shaped crackers often served with oyster stews and fish chowders, seems

to be MIA.

The online blog Kitchn has noted that Westminster Cracker Company in New England lays claim to an oyster cracker first made in 1828. Nevertheless, the distinctive Trenton crackers were made in 1847 by British immigrant Adam Exton, soon followed by fellow Trentonian Ezekiel Pullen in 1848, who sold them from a wagon on Trenton’s streets. His cracker company was purchased in 1887 and renamed Original Trenton Cracker Company. A series of sales eventually resulted in one company, which relocated to Lambertville in the 1970s.

A March 2019 article in The Philadelphia Inquirer lamented the disappearance of traditional oyster crackers and indicated that the OTC brand was sold to a company in Massachusetts which was seeking a bakery to make the crackers on modern equipment. Attempts to contact the company were unsuccessful.

But the crackers live on in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, which has compiled some of this information, and also in the memories of many who loved the classic, crunchy crackers with a bowl of steaming clam chowder.

Shore Souvenir: Salt Water Taffy

The colorful boxes of boardwalk salt water taffy you bought for your office, or for neighbors who took in your mail (with a small box for yourself), originated in the 1880s in Atlantic City and became permanent residents of the Jersey Shore.

The Atlantic City Exhibit at the Jim Whelan Boardwalk Hall, created in part by the Atlantic City Free Public Library, calls the taffy an Atlantic City innovation. The online exhibit cites a legend in which a storm soaked some taffy with salt water and the phrase caught on. The name was briefly trademarked, but it was found to be in common use by the 1890s.

A New Jersey merchant, Joseph Fralinger, of Sweetwater, is given kudos for his marketing. A glassblower who later ran an oyster business in Philadelphia, Fralinger moved to the Jersey Shore for his wife’s health. There, he managed some minor league baseball teams, and worked a variety of jobs until he was asked to take over a taffy stand on the Applegate Pier. It was his idea to box the taffies in one-pound boxes – a sweet success.

Competition came from Enoch James, who arrived with his sons in 1880, and developed a smoother recipe. James also cut the candy into bite-sized pieces, and is credited with mechanizing the taffy pulling. Both Fralinger’s and James’ stores still operate on the Atlantic City Boardwalk, both owned by the Glaser family since 1947, which proudly uses both original recipes. Shriver’s, the oldest business on the Ocean City Boardwalk, opened in 1898 – and offers 70 flavors of taffy.

Semantics: Pork Roll or Taylor Ham

Even President Obama invoked the pork roll/Taylor ham semantics debate in a 2016 commencement speech at Rutgers, refusing to take sides on the regional favorite.

Even President Obama invoked the pork roll/Taylor ham semantics debate in a 2016 commencement speech at Rutgers, refusing to take sides on the regional favorite.

It can be confusing. Taylor is the brand name for pork roll made by Taylor Provisions, Inc., of Trenton. Taylor ham is a common name for the pork-based processed meat. John Taylor, a politician, created pork roll in 1856. He formed Taylor Provisions Company in 1888, establishing the brand Taylor’s Prepared Ham, commonly called Taylor ham, sold in a burlap-covered roll.

Trenton is also the home of the family-owned Case’s Pork Roll, cured with hickory chips – the same recipe George Washington Case used for his first product in 1870. Trenton’s Mill Hill Park is the site of an annual pork roll festival each Memorial Day weekend (not held this year due to the pandemic) run by Trenton resident Scott Miller, who grew up on Lebanon, Pa., bologna, so pork roll was not a stretch, he says. (A competing festival is also held in Trenton.) Miller calls pork roll a “remarkable product.” The somewhat smokey and spicy pork is sliced, and then grilled or fried. Miller enjoys it thinly sliced and crispy, as a side order, or, like most New Jerseyans, in a breakfast sandwich with egg and cheese, on good bakery bread. However you slice it, New Jersey loves its pork roll, or Taylor ham.

Tart and Sweet: Cranberries and Blueberries

Blueberry pancakes. . . cranberry muffins. . . New Jersey’s role in providing fresh, plump berries is considerable. The Pinelands is one of the few places where cranberries grow naturally, according to New Jersey’s official website. Many incorrectly think that cranberries grow in water — they actually grow on low vines in sandy, acidic soil with a high water table, called a bog. Many of New Jersey’s cranberry farms are proudly operated by the same families that started the farms.

The state site credits a bog near Burrs Mill in Burlington County as the first cranberry farm in 1835. Harvesting used to involve gathering berries by hand, and, later, large wooden scoops were used. Since the 1960s, the bogs are flooded for the wet picking method which involves a machine with a water wheel. The tart cranberry has air pockets and floats to the top of the bog. New Jersey is annually among the top three producers of cranberries in the U.S. according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS).

Elizabeth Lee, of New Egypt, is said to have first made cranberry sauce in New Jersey in 1917, although Marcus Urann of Massachusetts made the sauce in 1912. But they joined together to develop what is now Ocean Spray, a growers’ cooperative. Its former Bordentown facility is now located in Upper Macungie, Pa.

The cranberry is not the only berry that puts New Jersey on the map. According to the Phillip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research and Extension, a substation of the Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station (NJAES), the first domesticated blueberry crop was cultivated in 1916 by another female grower, Elizabeth Coleman White, and botanist Frederick Coville on a farm that White’s family owned. White, of New Lisbon, helped organize the New Jersey Blueberry Cooperative Association. By 1986, New Jersey’s blueberry industry had become the second largest in the country. In 2004, the blueberry became the official state fruit.

Bottleneck: Boylan Birch Beer

In 1891, Pharmacist William Boylan created an elixir in his Paterson apothecary. He named it for a derivative of birch trees, Boylan’s Birch, and sold individual portions from a wagon. The Boylan Bottling Co. was known for distinctive long-necked, embossed glass bottles, not too much different from today’s look. The company was located in Haledon for about 50 years until 2001, and then relocated to Clifton before landing in Moonachie, Teterboro, and finally New York City.

Testimonials abound for the drink. A blog by the eclectic Muddy’s Bake Shop in Memphis, Tenn., heralds Boylan’s as a “worthy” accompaniment to their baked goods, a “craft soda” made in small batches. According to the New Jersey Bottle Forum, the Boylan family left the soda business for more lucrative liquids after Prohibition, but the business is still in the hands of the second family of owners.

Mm! Mm! Good!: Campbell’s Soup

Fruit merchant Joseph Campbell and icebox manufacturer Abraham Anderson made soup history when they became partners in 1869 in the firm of Anderson and Campbell in Camden, the firm that preceded The Campbell Soup Company, says Campbell’s spokesperson Amanda Pisano.

In the early years, the company canned Jersey tomatoes in addition to other vegetables, and made jellies, soups, condiments, and minced meats. Tomato Soup was introduced in 1895, initially using Jersey tomatoes. In 1897, general manager Arthur Dorrance hired his 24-year-old nephew, chemist John T. Dorrance, who invented condensed soup – which was easier to ship and store. In 1922, the company added the word soup to its official name. By 1990, the 20 billionth can of Condensed Tomato Soup was produced.

The company now employs 1,000 at its Camden world headquarters, says Pisano. It has grown to become one of the largest processed food companies in the U.S., with a wide variety of Campbell’s products, as well as brands such as Pepperidge Farm, Snyder’s of Hanover, V8, and Swanson.

During the pandemic, the company has addressed the issue of food insecurity and “donated more than $5.8 million to support our hometowns across North America and in the Camden area,” says Pisano, noting significant contributions to local organizations like the Food Bank of South Jersey, Cathedral Kitchen, the Salvation Army Kroc Center, Philabundance, and the New Jersey Pandemic Relief Fund, among many others. Campbell’s helped purchase laptops so Camden students can learn remotely, and this year, Campbell’s will be completing a 10-year, $10 million initiative to improve the health of Camden youth, according to Pisano.

Adopted: Kerr’s Candy

Kerr’s Butterscotch Candy, while made in Ontario, Canada, has been adopted as a Jamesburg resident candy. Kerr Brothers was founded in 1895 by Edward Kerr and Albert Kerr. Emigrating from Scotland, they opened a bakery and candy store in St. Thomas, Ontario, in 1898 and moved in 1904 to Toronto to be closer to suppliers. In 1907 the Kerrs expanded their operations and built a factory in Jamesburg, opening as Kerr’s Butterscotch Inc. They switched the packaging from paper bags to folding boxes and sales reached over 10 million bars after World War I, according to the company website. The Jamesburg Historical Association has an original candy wrapper.

Points of Pride

In 1912, Giuseppe Papa made a tomato pie. Today, Papa’s Tomato Pies in Robbinsville is said to be the country’s longest continuously operated family-owned pizzeria. (The New York Times in 2011 explained that Lombardi’s of New York, which opened in 1905, had closed for 10 years before reopening.) Joe’s Tomato pies in Trenton opened in 1910, but has since closed.

In the early 1900s, chemist Ben Faunce of Riverside, who sold his own brand of cough syrup, toothpaste, and other medications, concocted a recreational drink, Tak-A-Boost. It was registered with the U.S. Trademark office in 1913 and became The Boost! Company.

Trenton’s Allfathers, which began making Easter candy in 1882, is known for its coconut cream, yolk center eggs and other treats like a nine-ounce milk chocolate rabbit.