A “Shared Musical Dialogue”

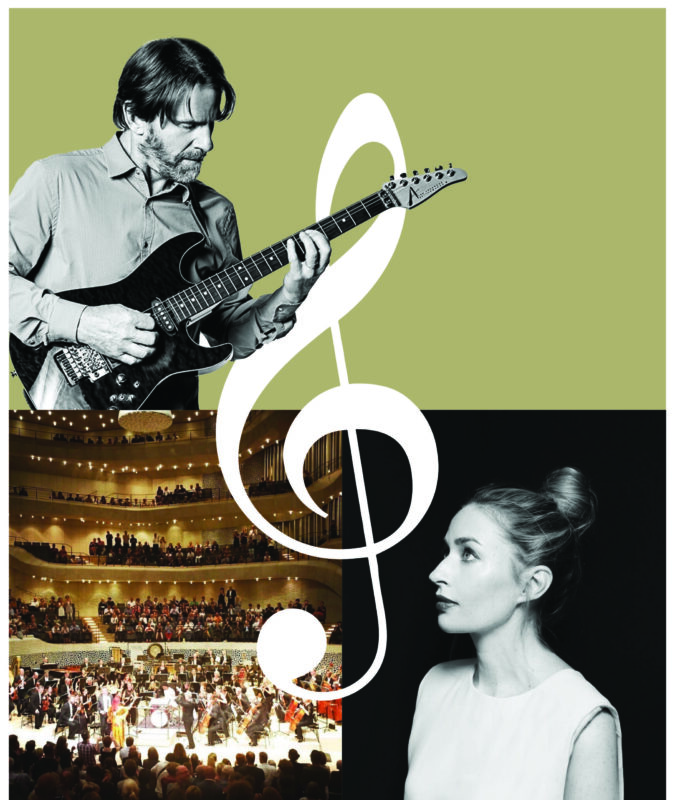

Steven Mackey. (Photo courtesy of Kah Poon, @kahpoonphoto); (Stage image courtesy of Sarah Kirkland Snider); Sarah Kirkland Snider. (Photo by Shervin Lainez)

Princeton Composers Sarah Kirkland Snider and Steven Mackey

By Donald H. Sanborn III

Born and raised in Princeton, composer Sarah Kirkland Snider writes music that The New Yorker has described as “genre-erasing.” Her website describes her music as an organic synthesis of a “diversity of influences to render a nuanced command of immersive storytelling.”

Her works have been commissioned and/or performed by the New York Philharmonic, the Birmingham Royal Ballet, and soprano Renée Fleming. The Washington Post named Snider one of the Top 35 Female Composers in Classical Music in 2019. Elsewhere, she has been cited by critics as “a significant figure on the American music landscape,” an “important representative of 21st century trends in composition,” and “one of the decade’s more gifted, up-and-coming modern classical composers.”

Snider is married to composer Steven Mackey. The couple live in Princeton with their son Jasper, 14, and daughter Dylan, 12.

Steven Mackey, right, with Alicia Olatuja, left, and the New Jersey Symphony, conducted by Xian Zhang, center. (Photo by Natalie Rakes)

Mackey was born in Frankfurt, Germany, and raised in northern California. Since 1985 he has taught at Princeton University, where he is the

William Shubael Conant Professor of Music. The University website notes that his “passion was playing the electric guitar in rock bands based in northern California. He blazed a trail in the 1980s and 90s by including the electric guitar and vernacular music influence in his concert music and he regularly performs his own work.”

He has been composer in residence at Curtis Institute of Music (2014-15). His work has been performed by ensembles such as the Kronos Quartet, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Accolades include the Kennedy Center Friedheim Award, an award in music composition from the American Academy and Institute for Arts and Letters, and a Grammy Award for Best Small Ensemble Performance.

“In Search of the ‘Right’ Wrong Note”

“For the first 20 years of my life, I was a blues/rock electric guitar player,” Mackey recalls, adding that when he was in college, a weekend visit to his older brother led to an unexpected discovery. “He put in this Beethoven tape; it was a scherzo from the last string quartet. As a blues guitar player, I was already in search of the ‘right’ wrong note — the ‘blue’ note that made you squirm, like the great blues guitar players like Buddy Guy or Jimi Hendrix.”

Steven Mackey at piano. (Photo by Natalie Rakes)

Mackey continues, “The movement begins with a sing-song-y little tune, and then it hits this E-flat. [The movement is in F major, a key in which E-flat does not belong.] The rhythm breaks down — everything breaks down in this tune. I almost fell out of the seat — it hit me so hard.”

He adds that at the time he felt a growing ambivalence about life as a rock performer — being asked to play other artists’ hits instead of his own material — and this “coincided with discovering this music that was intended to distill all of life into a listening experience. I said, ‘That’s what I want to do!’”

Sarah Kirkland Snider. (Photo by Willy Somma)

Asked when she knew that she wanted to be a composer, Snider says, “I think that as a woman, you’re going to have a different experience. Growing up before the internet, I didn’t know that there were female composers. So, I didn’t really think of it as a career option until much later. But I remember feeling my initial connection to music — feeling like music was the place in life where I felt the most myself — as a young kid, maybe in kindergarten.”

Snider continues that, growing up in Princeton, “I would walk for 15 minutes to and from school by myself, and during those walks I would have these fantastical musical excursions in my head.”

She remembers being inspired by film scores, and orchestral music that accompanied Tom and Jerry cartoons.

“But I think it would be a number of years later before I thought it could be a career option for me,” Snider continues. Mackey interjects, “In fact, she didn’t even think of majoring in music in college.” Snider confirms this: “I majored in psychology and sociology. I thought I was going to go into some kind of social work, or public sector legal work. In fact, I was a paralegal in New York for three years, before I had my first composition lesson, at the age of 25.”

On a Subway Platform After a Concert

Snider and Mackey met “on a subway platform — just chatting after a concert,” Snider recounts. She was perusing the program for a concert at Lincoln Center, given by percussionist Evelyn Glennie. “Steve was coming from Merkin Hall; he had been to see something else.” But Mackey had known that the Glennie event featured the music of composer Michael Daugherty, whom he was often compared at the time. “So, he felt this sort of quasi-competitive interest in what I thought of this piece,” says Snider.

As the conversation ensued, Snider discovered that she was talking to Mackey, whose music she knew and admired. “So, I was like, ‘You teach at Princeton; I’m from Princeton!’” she says. “We continued talking from there.”

Mackey adds, “I was on the board of the Princeton Symphony, and her parents were on the board.” At the suggestion of her mother, Snider consulted Mackey about possible graduate schools. “Sarah was interested in pursuing composition, but having not majored in music she didn’t have any former teachers that she could go to,” Mackey explains. “That was 20 years ago.”

Snider reflects, “We saw eye to eye about music, and about life and the world. We both grew up loving rock and pop music. While I never played in a band, I was obsessed, in my 20s, with going to indie rock performances. So I would be writing a string quartet during the day, and going to see all these bands in New York at night.

It felt like living a double life, and Steve felt the same way about repressing his rock background in his early years as a 12-tone composer.”

The couple bonded over a mutual desire for a musical climate in which they felt that they were free to explore all of their musical interests in their compositions, without self-censorship. “I think we both figured out how to do that in our music, over time. But we inspired one another to push for greater honesty in our music,” says Snider.

A “Shared Musical Dialogue”

Asked whether Mackey and Snider influence each other’s compositions, both composers simultaneously answer, “Absolutely.”

Snider considers the “day-to-day aspect of playing our music for each other. When we’re composing, we share a lot of our MIDI files with each other. We’ll listen and discuss what we’ve written that day.”

Mackey interjects, “She’ll play something for me and I’ll go, ‘That sounds a little like Mackey!’ And she’ll listen to something that I’m writing and remark, ‘There’s a little bit of me in that line!’”

Snider says, “We have become, in some ways, each other’s ideal listener. It’s like having the benefit of a composition teacher, but so much richer because there’s a sense of equality and mutual respect between us that’s wonderful. It has been a cornerstone of our closeness over the years — this shared musical dialogue.”

Asked whether Jasper and Dylan are musically inclined, Snider replies, “They are, in fact. When the kids were young, we thought, ‘We’ll expose them to music, and suggest that they study an instrument. But we’re not going to put too much pressure on them, because they have two professional composers for parents.’”

“They’ve each gravitated to music on their own,” she adds. “We started our kids in violin; they didn’t want to do that. Jasper moved toward drums, and Dylan moved toward piano and singing (although she plays some drums, too). Now, Jasper is also an electric guitarist; he’s giving his dad a run for the money, I have to say!” Mackey concurs.

Snider says that Dylan is “writing lots of music for piano.” Mackey adds, “She’ll sit down at the piano and say, ‘Give me a word.’ If I say ‘avalanche,’ then she’ll improvise on the word ‘avalanche’ — which is a very composer-ly thing to do.”

Compositional Styles

“There’s this wonderfully open-hearted, direct quality that Steve has at times, which is earnest and heart-on-its-sleeve,” Snider says when asked to describe Mackey’s compositional voice. “I’m thinking of Turn the Key, which he wrote for New World Symphony a few years ago. It has these tunes that are jubilant.”

Of her own compositional style, Snider says that her music often is described as “emotionally direct.”

She continues, “We’re here for so short a time, why not say something honestly and directly? I think my music tends to be quite layered and contrapuntal — but stylistically, there’s quite a spectrum. Some of my pieces are to the classical side of my upbringing and experience (growing up playing in orchestras), and others are more to the indie rock side of my musical background. But I think all of my music aspires to tell a narrative, and I use whatever stylistic means seem the best equipped to tell that story. So I like working with a wide stylistic toolbox.”

Of Snider’s compositional style, Mackey says, “Beauty comes to mind. It’s contrapuntal, so it’s a complex interweaving of trajectories, and it’s hard to pull that off. She’s at the height of her powers now, so she’s pulling it off in the way that Bach pulls it off, with these overlapping lines. But at the same time, there’s a clear sense of line, character — as she says, narrative.” He offers that Snider’s work explores how “these musical characters interact and evolve.”

“Also, there’s always a beautiful, bittersweet quality to her music,” Mackey adds, remarking that while his music often has “optimism and energy, her music has a bittersweet melancholy under the surface, which is beautiful.”

Upcoming Performances and Future Projects

On August 5, Snider’s Something for the Dark will receive its Cleveland Orchestra premiere. Snider says that the work, which originally was commissioned by Detroit Symphony, is inspired by a poem by Philip Levine, and explores “resilience, hope, and renewal.”

A month later, Princeton Symphony Orchestra will open its 2023-2024 season on September 9 with Forward Into Light. According to Snider’s website, Forward Into Light is a “meditation on perseverance, bravery, and alliance. The piece was inspired by the American women suffragists,” though the piece “does not attempt to tell the story of the American women’s suffrage movement, but rather to distill the emotional and psychological contours of faith, doubt, and what it means to persevere.”

The titles Something for the Dark and Forward into Light suggest that the pieces are related, but Snider says that they are not.

“Forward into Light was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, as part of their Project 19 commissioning program, which was to celebrate the women’s suffrage centennial,” she explains. “They commissioned 19 female composers for chamber and orchestral pieces.”

“So, I wrote this 15-minute piece about the emotions that galvanize a person to endure all of the hardship that the suffragists endured in order to campaign for their rights to vote,” Snider continues. “I think of the piece as an emotional trajectory about what it means to persevere. It’s my favorite orchestral piece that I’ve written so far. For me, it felt like a significant step forward, compositionally; I tried some new things, and had a lot of fun writing it. So I’m very excited to have the Princeton Symphony perform it!”

Currently, Snider is at work on an opera about Hildegard of Bingen, for which she is writing the libretto as well as the music. It will be conducted by Gabriel Crouch, conductor of the Princeton University Glee Club.

“Gabriel and I are going to be teaching a course on my opera in the fall, as part of the Lewis Center for the Arts’ Princeton Athelier program,” Snider says. “That will result in a workshop at the University.”

This past April, Mackey’s RIOT was presented at a New Jersey Symphony concert titled “Mozart & Steven Mackey.” Mackey explains that RIOT was “commissioned by the New Jersey Symphony to celebrate their 100th anniversary. The piece is a grand statement; since I sang the Berlioz Requiem in the college choir when I was an undergrad, I’ve wanted to write a piece with 200 people on stage. RIOT is my realization of that fantasy. You’ve got the University Glee Club; the New Jersey Symphony; and vocalist Alicia Olatuja, who can sing like a classical mezzo-soprano, or like a jazz singer. She’s very comfortable with a microphone, which I explore.”

From July 9-15 the Edward T. Cone Composition Institute, which Mackey directs, will take place in Princeton.

“New Jersey Symphony comes; we bring four young composers from all over the world to workshop their music with the orchestra, and then the orchestra also does an (as yet undecided) piece of mine,” Mackey explains.

The concert is on Saturday, July 15 at 8 p.m. in Richardson Auditorium. According to the orchestra’s website, the “performance will be conducted by Case Scaglione. The Institute is presented in collaboration with the Princeton University Music Department.”

Advice for Aspiring Composers

Asked what advice he would give to aspiring composers, Mackey says, “The older and more experienced I’ve become, I’ve realized that to sustain a career as a composer, you need to stand for something. A friend of mine, conductor David Robertson, was asked why he decides

to program one piece and not another. His answer was, ‘I want to see that only that composer could have composed this piece.’”

Rephrasing that comment for his students, Mackey warns against self-censorship: “If there’s music that you love, you should find a way to show that love in your music. If you think, ‘I’ve got to do what’s allowed,’ you will be like a lot of other composers that are conforming. If you want to stand for something, you’ve got to let all the warts and pimples come out — and be yourself!”

Snider agrees, and adds that it is important for composers to find a mentor or other support network for encouragement, because composing “can feel like you’re constantly wishing you had more ideas, or could be quicker. You’ve got to push through … so much self-doubt. This is something I talk about with young composers — finding your support network, whether it’s a partner, a great mentor, or your friends. Being able to talk about the angst of composing is important and helpful.”

Mackey adds that when students ask whether they are “allowed” to explore a certain musical idea, he tells them, “‘You don’t need composition lessons; you need therapy.’ As a teacher, you try to convince students, ‘Your ideas are good enough, so pursue them!’”