School Days

By Stuart Mitchner

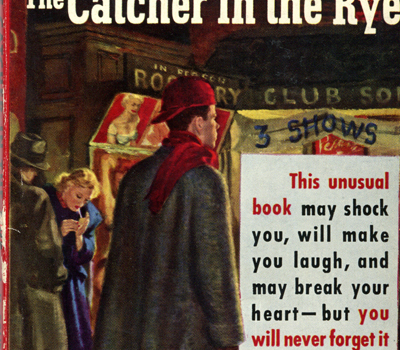

Every time the “back to school” theme comes up, I think of The Catcher in the Rye, New York City, and the year I went to McBurney School on 63rd Street off Central Park West. I was 16 when I read Holden Caulfield’s story for the first of many times, not knowing that J.D. Salinger had been at McBurney decades before me and that some of Holden’s school experiences and relationships were drawn from his two years there.

On that first reading, I was struck by Holden’s mention of a fencing meet with McBurney School that never happened because, being manager of the Pencey Prep fencing team, he’d left the equipment on the subway (“It wasn’t all my fault. I had to keep getting up to look at this map”). So, even before I knew we had McBurney in common, there it coincidentally was, out of all the schools Salinger could have named. The passing mention of the school and the subway gave me an connection to Catcher beyond what was already a love-at-first-sight reading experience.

Years later when I found that Salinger had not only gone to McBurney but had managed the fencing team, it was a thrill to discover that someone I admired more than any living author could well have shared the same morning ritual of a subway ride to Columbus Circle and the three block walk up Central Park West. Since his family lived in an apartment house on Park Avenue and East 91st at the time, Salinger would have taken IRT’s Lexington Avenue Line from 86th and changed to a crosstown train. From where I lived on East 53rd near Third Avenue, I took an IND train to Seventh Avenue, changing there for Columbus Circle. It sounds simple enough, but the morning rush hour for a kid from Indiana was a big deal: the daily battle to fight your way on and off packed trains before the doors slammed shut, and to come to school still reeling after being pressed face to face and body to body with a sweaty heaving mass of humanity in that super-intense zone of subway noise and motion.

Walking through the Boy’s Entrance at McBurney was not something a ninth-grader from the midwest ever took for granted. The 14-story West Side YMCA building occupied by the school resembled a “castellated Italian hill town, with towers, battlements and balconies rising in irregular sympathy, culminating in a huge, central tower with an octagonal roof,” according to New York 1930 (Rizzoli 1987). “Above the base the building’s masses stepped back with loggias and hipped tile roofs.” Reference is also made to Gothic and Romanesque details and “the extensive use of polychromed terra-cotta.” Inside, the architect Dwight James Baum sustained the “medieval Italian theme … with studded plank doors, concrete beams painted and decorated in imitation of wood, rough plaster walls, medieval-style furniture and polychromed tilework.”

Quite a change after three grades in a two-room red brick schoolhouse in the woods of southern Indiana.

When McBurney closed its doors in 1988, there was an auction of the contents. A story in The New York Times describes buyers looking for old yearbooks containing photos of future celebrities. While Salinger remains the most illustrious McBurneyan, two actors known for playing tempermental opposites on television went there: John Boy of The Waltons (Richard Thomas) and The Fonz from Happy Days (Henry Winkler). Although McBurney had other noteworthy alumni, including Felix Rohaytan, chair of the Municipal Assistance Corporation, and Ted Koppel of Nightline, it “may be best remembered,” according to the wikipedia entry, “as the destination of Holden Caulfield when he left all the equipment of the Pencey Prep fencing team on the subway.”

CELEBRITY ALUMNI

In New York, almost every school, public or private, big or small, can claim celebrity alumni. It’s a form of what CUNY Sociology professor William B. Helmeich calls “community cachet” in The New York Nobody Knows: Walking 6000 Miles in the City (Princeton University Press $29.95). One example is the naming of West 84th Street after Edgar Allan Poe. Another is P.S. 199 on Shakespeare Avenue in the West Bronx, which is known as the Shakespeare School and presents a play by the Bard every year in June. P.S. 149 on Sutter Avenue in East New York is known as the Danny Kaye School, after the comedian. Then there’s the West Harlem School on Edgecombe Avenue and 165th Street which features a mural depicting famous alumni, a diverse mixture that includes Diana Sands, who starred in Raisin in the Sun; singer Harry Belafonte, and economist and Federal Reserve chair, Alan Greenspan.

All the moral bases are covered at Washington Irving High School on Irving Place, from movie stars Paulette Goddard and Claudette Colbert, radio/television legend Molly Goldberg and The View’s Joy Behar, to porn star Asa Akira, rapper Vast Aire, and computer hacker Hector Xavier Monsegur (Sabu). But it’s hard to top Erasmus Hall High School on Flatbush Avenue in Brookyln, where the alumni list includes chess champ Bobby Fischer, artist Elaine de Kooning, movie star Susan Hayward, Moe Howard of the Three Stooges, novelist Bernard Malamud, Neil Diamond, Beverly Sills, Mickey Spillane, Barbara Stanwyck, Barbra Streisand and Mae West, and that’s a very selective list.

Helmreich’s example of the other side of community cachet is Cypress Hills in Brooklyn, bordering East New York, where just to the right of P.S. 65’s “Corinthian pillars” and the “decorative cement shields” above the entrance “a lonely pair of kids’ sneakers dangles on a telephone wire.” Posted on the stairs are “various exhortations” such as “Work hard to be nice,” ‘Raise the bar,” and “We are climbing the mountain to college.” As Helmreich observes, “a mountain it is, indeed” in a place like Cypress Hills.

The base of the statue of Erasmus in front of Erasmus Hall is inscribed, “Desiderius Erasmus, the maintainer and restorer of the sciences and polite literature, the greatest man of his century, the excellent citizen who, through his immortal writings, acquired an everlasting fame.”

In 1994 Erasmus Hall H.S. closed “due to poor academic scores.” In 2011 the New York City Department of Education announced that Washington Irving H.S. would be closed by summer 2015. At the time Hector Xavier Monsegur was attending, only 55 percent of the students graduated with their classes.

TEACHERS

Some of the best-known accounts of New York City schools come from former teachers. Generations of readers and moviegoers have read or seen Evan Hunter’s Blackboard Jungle, which was based on the author’s 17 days teaching at Bronx Vocational High School, and Bel Kaufman’s Up the Down Staircase, which reflects Kaufman’s experience teaching at various city high schools. Hunter, whose real name was Salvatore Lombino, also wrote under the name Ed McBain. He took his schooling seriously enough to base his pen name on his two alma maters, Evan for Evander Childs High School and Hunter for Hunter College, which was also Bel Kaufman’s alma mater.

Among the most engaging teacher memoirs is Frank McCourt’s Teacher Man (Scribner 2005), which begins with McCourt in his mid-twenties teaching at Staten Island’s McKee Vocational and Technical High School, where on his first day he was called into the principal’s office for picking up a sandwich one student had thrown at another and then eating it while the class watched. It was his “first act of classroom management,” and it was no chore: “The bread was dark and thick, baked by an Italian mother in Brooklyn, bread firm enough to hold slices of rich baloney, layered with slices of tomato, onions and peppers drizzled with olive oil and charged with a tongue-dazzling relish.” So began the first of the 33,000 classes McCourt estimates teaching in thirty years divided between McKee, Seward Park High School in Manhattan, Stuyvesant High School, and night classes at Washington Irving.

The conflict between an inventive “classroom management” style like McCourt’s and a clueless or dictatorial administration is also played out in John Owens’s Confessions of a Bad Teacher: The Shocking Truth from the Front Lines of American Public Education (Sourcebooks 2013), which recounts the author’s struggles teaching English at a public school in the South Bronx.

“THE LAUGHING MAN”

Before he attended McBurney, J.D. Salinger went to public schools on the Upper West Side, including P.S. 165 on 109th Street near Amsterdam Avenue, as he notes in the opening paragraph of “The Laughing Man,” one of his most autobiographical stories. The hero of the story is a young law student from Staten Island who has been hired by the parents of the narrator and his 25 classmates to drive them around after school in a bus; when the weather is suitable, he takes them over to Central Park after school to play football or soccer or baseball. On rainy afternoons, the Chief, as his charges calls him, shepherds them to the Museum of Natural History or the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After the playing is over and they’re back in the bus, the Chief tells them an ongoing narrative for which the story is named. Like most good stories, Salinger’s comes with complications, a love interest, and a sad, thoughtful ending.

The school at 109th and Amsterdam is still in business, but judging from the parent-teacher blog, the situation there is dicey, to say the least, and all indications are that the issues raised in John Owens’s book are the reality: committed teachers and a struggling administration. The demographic is 70 percent Hispanic, 15 percent black, ten percent white, and three percent Asian.

On the P.S. 165 Robert E. Simon website is a photo of the entrance through which nine-year-old Jerry Salinger presumably came and went. I have been unable to find out what Robert E. Simon’s contribution is or was. The P.S. 165 home page says, “Dare to dream, to achieve, to make a difference.”

Like McBurney, P.S. 165 should be best remembered for its relation to the life and work of a great American writer who dared to dream and make a difference. It’s a connection the school should make more of, since P.S. 165 is obviously in serious need of what William Helmreich calls “community cachet.”

Comments ( 0 )